Why The Technology That Saved Us Time Is Stealing Our Lives!

What I learned from being the city's most stubborn Luddite!

My husband held up his Nokia like it was evidence in a trial where I was the defendant.

Him: “You need a phone. Why don’t you just get one? Everyone has one.”

Me: “I have a phone. There’s one in the apartment.”

Him: “A cell phone.”

Me: “Why would I need a phone that follows me around?”

He stared at me the way you’d stare at someone who just suggested we communicate via carrier pigeon or something. We were crammed into our Richmond Hill apartment, and it was 2006, which apparently made me the last human in the tristate area without a mobile device. I was a dinosaur. A relic.

Him: “What if there’s an emergency at your new job? What if there’s another blackout?”

Fair point.

I’d started a new job that had me traveling more. But there was a deeper message tucked inside his words, and it wasn’t easy to digest: You need to catch up. With here. With America. With how things work when you’re trying to make it in a country that moves faster than the one you left behind.

About That Blackout

Three years earlier, in August 2003, I was one of those people you saw in grainy news footage, walking across the Triborough Bridge in a river of bewildered, sweaty humanity. The Great NYC Blackout trapped me downtown. There was no power. No subway. No way to tell my husband I wasn’t lost or spontaneously combusting in the August heat.

You’d think that would’ve sent me sprinting to the nearest Verizon store.

Nope.

I finally caved in 2006 because my husband wore me down. Men have this gift for turning one harrowing experience into a lifetime subscription to their anxiety. One blackout, and suddenly I needed to be trackable at all times. For my safety, naturally. Definitely not, so he could call and ask where I put the scissors.

The Island Where Time Moved Differently

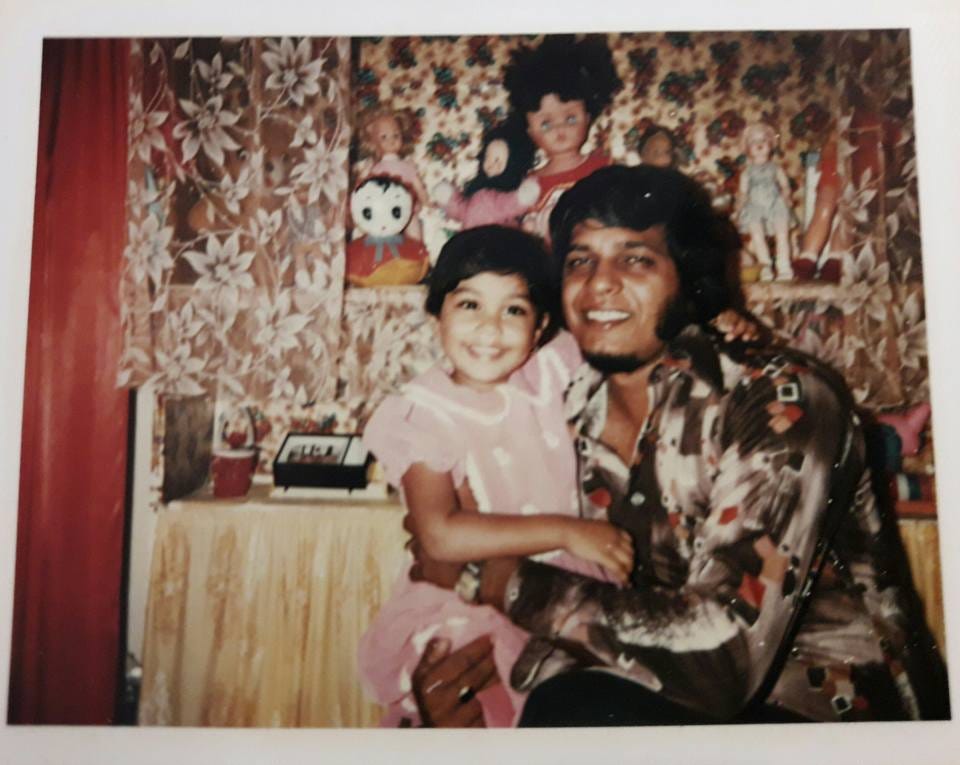

I grew up in Trinidad and Tobago, where talking face-to-face was just how you did things. My parents didn’t see the point of a landline. If my dad had news, he’d drive over in his trusty Nissan to tell you in person.

These weren’t quick drop-ins either.

Messages became conversations. Conversations became someone putting on a pot of Hong Wing coffee. Coffee became cheese paste sandwiches. Sandwiches became pulling up chairs and settling in until the mosquitoes clocked in for their evening shift and someone finally said, “Lord, look at the time.”

Those were the good old days.

My grandparents didn’t get a rotary phone until ‘87. I was around twelve and couldn’t have cared less. And really, what would you have chosen? A plastic beige box sitting on a crocheted pink doily, or being outside in the mango tree, fingers sticky with juice? That phone rang only often enough to remind us it was alive.

Then I got my first boyfriend.

Dennis.

At ten, I was convinced we were soulmates, which my grandfather found hilarious. Suddenly, that rotary phone was the coolest thing ever.

I’d practice dialing his number when no one was watching, seeing how fast I could spin that dial. My finger went around, waiting for it to spring back. Seven numbers felt like years when you’re ten and desperate to hear someone’s voice, every second stretching like taffy.

The Physics of Presence

There’s this study from the University of Essex from 2012. Just having a phone visible during a conversation reduces the quality of the interaction. The researchers called it a “reminder of the wider social network” that prevents genuine connection.

That’s why when humans walk into my workspace, my phones go straight into the drawer. In fact, during the weekdays, I check my personal phone in the morning and maybe once in the late afternoon.

There’s always some family group chat happening, someone asking if we remember the name of that cousin’s dog from 1998, someone else posting a recipe nobody will make. It’s never urgent. It’s never even close to urgent. But it has this gravitational pull, this insistence that there’s something just slightly more interesting happening elsewhere. And I can’t afford that lie. Not if I want to do actual work. Not if I want to pay my rent.

A few months ago, I went to a Nine Inch Nails concert in Los Angeles. A hundred and fifty bucks per ticket. Not cheap seats.

The mother and daughter directly in front of me spent the entire show on their phones. Four and a half hours. They weren’t filming. They were just... scrolling. Through what, I have no idea. Instagram? Email? The void?

Meanwhile, ten feet away, Trent Reznor was doing that thing he does where he transforms decades of rage and loneliness and beauty into sound so physical you feel it rearranging your organs. And they were looking down.

I kept waiting for them to look up. To remember where they were. They never did.

I felt this sad, disoriented feeling wash over me, just this deep confusion about when we all signed the contract that says the thing happening right in front of us is never quite enough. That reality itself has become a placeholder for whatever’s glowing in our pocket.

The Great Rewiring

In 1964, Marshall McLuhan wrote that “the medium is the message”- that the technology itself shapes us more than the content it delivers. He was talking about television then, but he might as well have been writing about smartphones. The device doesn’t just deliver information. It restructures how we think, how we connect, and how we exist in time and space.

Nicholas Carr later expanded on this in The Shallows, documenting how the internet is rewiring our brains- making us better at skimming and multitasking but worse at deep thinking and sustained attention. We’re becoming excellent at processing information and terrible at absorbing meaning.

But I think it’s uglier than that.

We’re losing the ability to be where we are.

We’re always half in the future, anticipating the next notification. Half in the past, reviewing what we should’ve said. Half in some alternate timeline where we posted the perfect response.

Everywhere and nowhere, all at once.

The Moment We Crossed Over

Somewhere around 2007, when the iPhone launched with its sleek touchscreen and its promise of the internet in your pocket, we crossed a threshold. Before that, technology was something we used. After that, it became something we inhabited.

Think about it.

In 2006, if you pulled out your phone mid-conversation at dinner, you were rude. It was an insult. By 2016, if you didn’t have your phone out at dinner, you were probably hiding something. Cheating, maybe. Or worse, not documenting the meal for Instagram, which meant did dinner even happen?

The social contract flipped in less than a decade, and most of us didn’t notice we’d signed a new one.

Look, I’m not saying we should all chuck our phones in the ocean and return to rotary dials. That ship sailed, and I’m not delusional. But I do think we need to reckon with what we’ve lost. We need to name it, acknowledge it, mourn it a little.

When I was trapped in Manhattan during the blackout, wandering through streets with hundreds of other people, something unexpected happened. People talked. Strangers shared information, water, battery-powered radios, theories about what had happened, and how long it would last. We became, briefly, a community bound by shared circumstance and shared helplessness.

Scary? Sure.

Disorienting? Absolutely.

Hot as hell? You bet.

But it was also kind of awesome in the original sense of the word, full of awe.

During the pandemic, people were isolated in their homes, phones in hand, more “connected” than ever. Zooming, FaceTiming, texting, posting. And loneliness rates hit all-time highs. Depression spiked. Anxiety became the baseline mood.

We were together and alone.

Connected and isolated.

Talking constantly but saying nothing.

The phone won’t give you back your attention. You have to take it back using both hands. And that’s harder than it sounds because we’ve been trained, with all the sophistication of a billion-dollar industry, to believe that being disconnected means missing out.

But missing out on what, exactly? Another notification? Another piece of information you’ll forget in ten minutes?

The Rotary Phone Principle

My grandparents’ rotary phone sat on that doily for twenty years. It served its purpose with minimal drama. It connected people when they needed connecting, when something important had to be said.

Then it got out of the way and let us live.

That’s the key. It got out of the way.

These days, I have two cell phones, one for personal, one for work, like I’m running a drug operation or having an affair or just trying to maintain some boundaries in a world that no longer believes in them. But I do most of my social media on my laptop. Substack, Medium, and LinkedIn are all on my computer. I have VERY basic apps on my personal cell.

It’s a small act of resistance, but it helps manage my time better. The laptop doesn’t follow me to the bathroom. It doesn’t buzz in my pocket during dinner. It can’t wake me up at 3 a.m. with news I don’t need until morning.

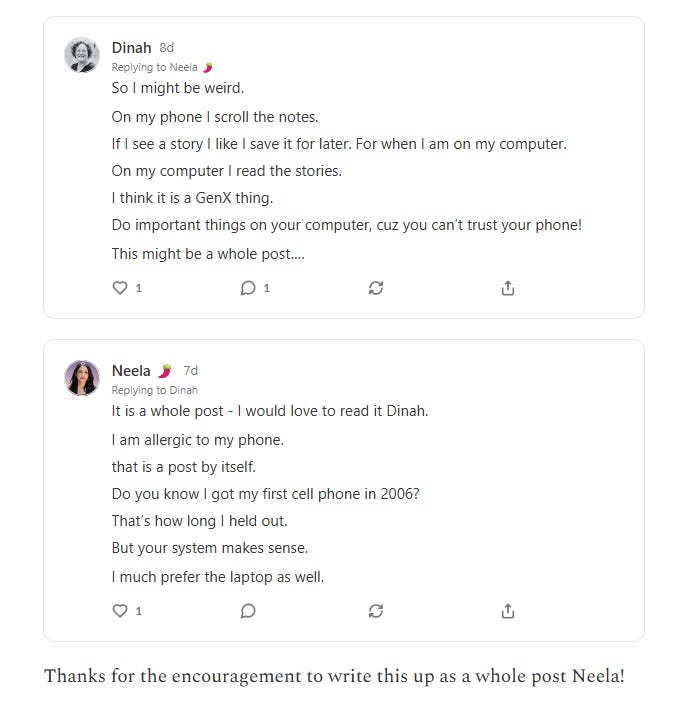

My friend Dinah, who inspired this article, told me about her system: On her phone, she scrolls through the notes. If she sees a story she likes, she saves it for later. For when she’s on her computer. “I think it is a GenX thing,” she said. “Do important things on your computer, cuz you can’t trust your phone!”

I’m allergic to my phone. That might be the most honest way to put it.

The Drives My Father Took

Sometimes I think about those evening drives my dad used to make, delivering messages that could’ve been phone calls. The magnificent inefficiency of it all. The time it took. The gas he burned.

He’d drive across town to tell someone something that could’ve been conveyed in thirty seconds. Then he’d stay for however long it took. They’d talk about the message, sure, but also about everything else. Family. Work. The weather. That thing they both saw on the news. The price of tomatoes. Nothing and everything.

Understanding how much my dad changed in those later years, the gambling, the losses, the alcohol, the slow erosion of the man I knew, these memories of inefficiency are all I have left.

I think about that word a lot now. Inefficiency.

In our current vocabulary, it’s practically profanity. We’ve built an entire civilization around eliminating it. Every app, every life hack, every productivity guru is selling the same promise: more output per unit of input.

But what if inefficiency was the point?

In Walden, Thoreau warned that we’d become “tools of our tools.” He wrote that in 1854, before electricity, before phones of any kind. He saw it coming. The way we’d surrender our time and attention to whatever promised to save us time and attention.

And that’s the problem!

We’ve figured out the striving part. But we’ve forgotten the being part. The part where you actually exist in the moment you’re in.

And so we end up with this strange paradox: striving that goes nowhere because we’re never present enough to know where we are or why we’re headed there in the first place.

The real conversations go unhad. The mango tree stands there, waiting.

Look Up

The tree is still there, by the way. Behind my grandparents’ house. I visited last year. It’s more gnarled now, the bark darker, branches reaching in directions that don’t make sense until you realize they’re following decades of sun and wind patterns I’ll never understand. But it’s still producing Julie mangoes every season. It’s still doing the thing it’s been doing since before I was born, the thing it’ll keep doing long after I’m gone.

It doesn’t need updates. It doesn’t have notifications. It’s never once asked for my attention.

It just grows.

We’ve engineered that capacity right out of ourselves. We’ve become so responsive, so available, so connected that we’re barely here at all.

Annie Dillard once wrote, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

Here’s what I’m asking, and I know how it sounds: Look up.

Not metaphorically. Actually look up from whatever screen you’re reading this on. See what’s around you. The room you’re in. The sounds you’ve been filtering out. The people nearby who might actually want to talk to you about the price of tomatoes or that thing on the news or nothing at all.

The real world is still out there, still happening, still waiting.

The question isn’t whether it’s there.

The question is: are you?

Thanks for sticking around. I mean that. You could’ve been scrolling.

WorkmanShit is a reader-supported publication.

To support my whisky habit, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

No cash? No problem!

Smashing that ❤️ button or sharing this post keeps the wheels on this greasy hamster wheel, too.

Well my system for Substack changed this weekend.

I was feeling like I was on substack all the time.

First thing I did in the morning? Check Substack.

Had a spare 2 minutes waiting somewhere? Check Substack.

Not just reading stories or notes, but also check my stats, as if they would be changing that fast.

Well this weekend I decided I needed some space.

I love writing my long posts, I also like interacting with people, but I don't need to do it at a moments notice from anywhere.

So for now I have removed substack from my phone and I changed my settings to get long form posts delivered via email so I can choose to read those on my phone or not.

No more checking my stats non stop.

And you know what? I feel calmer.

When I am on substack on my computer I enjoy it more. For now no substack on my phone is a good boundary.

Also a good chat with Neela about all of this on Saturday was also very helpful! She's amazing if you haven't noticed.

Neela this is a fantastic post to remind us that not everything needs to be done on a phone, and there is a whole world outside of that!

Nice post, Neela. You captured the nostalgia of the pre-cell phone days well, and you brought it back to the loss of connection. The story about your dad making sure everyone stayed connected really landed. Sounds like you learned something important there. Maybe that is why you like the squirrels outside your place so much. You envy their connection and their freedom :)